Jean-Martin Charcot’s biography. Introduction

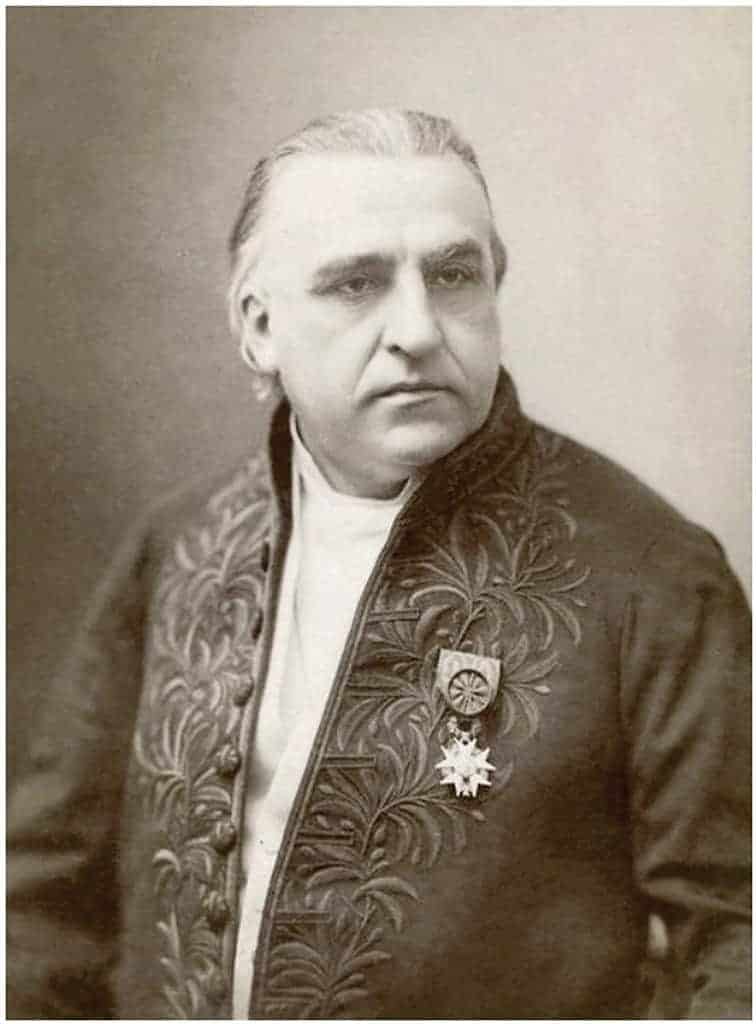

Appreciated by kings and princes, Jean-Martin Charcot was the most famous physician of his time, adopting the nickname “Napoleon of Neurosis”.

Charcot started his scientific studies in the field of internal medicine and anatomo-pathology. His research helped in understanding kidney and lung diseases.

Later his interest shifted to neurology. He studied neurological diseases developing a classification system based on symptoms observation and their comparison with the anatomical findings. He became internationally renowned for identifying Multiple Sclerosis (MS), Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), and raising awareness of Polio and describing Parkinson Disease.

However, Charcot’s third area of interest, the studies on hypnosis and hysteria, immortalized his name and created the foundation for the development of psychoanalyses. As a young physician Freud participated in Charcot’s lectures, translated some of his work into German and called his son after Charcot’s first name.

Charcot enjoyed significant authority and influence in English medical circles and great popularity in Russia. He was called upon multiple times to serve as a consultant physician to the czar and his family. Russian physicians welcomed him as he liberated them from their heavy reliance on German scientists.

L’Hôpital Salpêtrière

Salpêtrière was a vast 40-hectare complex with buildings, streets, squares, gardens, and the living place for 5,000 destitute, lunatic, senile, and insane women. The institution held historical significance, having been associated with Saint Vincent de Paul’s charitable endeavours. It was later transformed by Louis XIV into an asylum for beggars, prostitutes, and the mentally ill. The infamous September Massacres of the French Revolution took place there. It was Salpêtrière where Pinel implemented revolutionary reforms in mental healthcare liberating the mentally ill from chains.

As a young doctor Charcot began his internship at L’Hôpital Salpêtrière, affectionately known as “the great asylum of human suffering.” Later he became the leading physician in the hospital. Under his leadership, Salpêtrière became a major centre for neurological and psychiatric research paving the road to further discoveries in the dynamic psychiatry.

Reshaping Salpêtrière

Assigned as an interne medical resident, young Charcot spent time at Salpêtrière and recognized the hospital’s scientific potential.

For most doctors Salpêtrière was a hell and they tried to avoid working there. However, for Charcot as a passionate neurologist this environment was a paradise. He saw this place as a valuable resource for researching rare and unidentified neurological diseases.

While his medical journey progressed slowly and laboriously, a pivotal moment arrived in 1862. At the age of thirty-six, Charcot assumed the role of chief physician in a significant section of Salpêtrière, reigniting his ambitious plans with fervent dedication. He diligently recorded case histories, conducted autopsies, and established laboratories, simultaneously assembling a team of dedicated collaborators. Over the course of two decades, he introduced laboratories, museums, research rooms and teaching units.

In the span of eight years, from 1862 to 1870, Charcot made groundbreaking discoveries that catapulted him to become the leading neurologist of his era.

Charcot’s Private Life

Charcot’s was born after the French Revolution as a son of a Parisian coachmen. In order to overcome financial constraints, his father decided that the most gifted of his sons would study at a university. Martin surpassed his three brothers and in 1848 completed his medical studies at the University of Paris. In 1862 he married and became the father of two children.

His marriage to a wealthy widow and the substantial fees he charged his patients allowed him to lead a life befitting the wealthy class. Aside from his villa in Neuilly, in 1884 he acquired a splendid residence on Boulevard Saint-Germain, meticulously decorated according to his own plans. Harmonious and happy, his family life involved his supportive wife, a widow with a daughter, who actively assisted him in his work and engaged in charitable organizations.

Great care was given to the education of his son Jean, who to please his father become a physician and brought immense joy to Charcot with his initial scientific publications.

Prince of Science

Charcot personified a “prince de Ia science” in the French sense, possessing not only a high scientific reputation but also significant power and wealth. Charcot’s residence resembled a private museum adorned with Renaissance furniture, stained-glass windows, tapestries, paintings, antiques, and rare books. Charcot’s artistic prowess extended to excellent drawings and expertise in painting on china and enamel.

His passion for art history and masterful command of French prose showcased his profound knowledge of French literature. Remarkably, he possessed rare linguistic skills in English, German, and Italian. He admired for Shakespeare, whom he often quoted in English, and Dante, whom he quoted in Italian.

The public figure

Every Tuesday night, he hosted lavish receptions in his splendid home, inviting the crème de la crème of scientists, politicians, artists, and writers. With artistic inclinations and a large collection of old books on witchcraft and demonic possession, he proved an attractive teacher.

Among his fruitful clinical efforts, Charcot devoted Thursday evenings to his passion for music and strictly forbade any discussion of drugs during those hours. He loved animals and stood out from many of his peers in that he categorically refused to experiment with them. His distaste for the English is said to have been fuelled in part by their fondness for fox hunting.

Charcot was a frequent traveler, meticulously planning annual journeys to different European countries. During these trips, he visited museums, made drawings, and wrote travelogues. Despite his already immense prestige, Charcot was shrouded in an air of mystery, which gradually grew after 1870 and peaked with his renowned paper on hypnotism in 1882.

Charcot’s affection for animals

Despite being described as cold, reserved, austere, and impatient in his interactions, Charcot harboured a deep affection for animals. Notably, at his residence on 217 Boulevard Saint-German, Paris, he kept two dogs named Carlo and Sigurd, along with a beloved female monkey named Rosalie. Rosalie, a gift from Dom Pedro II, Emperor of Brazil, belonged to the species Cebus apella, known for their intelligence, friendliness, and playful nature.

An amusing tale mentioned in the renowned book “Charcot: Constructing Neurology” by Goetz et al., involves Rosalie’s mischievous antics during a dinner attended by esteemed international figures. The monkey managed to climb onto the elegantly adorned dining table and dismantled the centerpiece. Surprisingly, instead of causing distress, the incident fostered a sense of ease among the guests.

Charcot’s peculiar moral standard

Charcot’s fondness for animals went beyond mere professional concern and reflected personal ethics. He opposed hunting, bullfighting, vivisection, and experiments involving animals at La Salpêtrière Hospital. A sign in his office proclaimed, “You will find no dog laboratory here.” This stance stood in contrast to his profound interest in conducting autopsies on deceased patients at the hospital, which led to significant discoveries in the field of neurology.

Charcot’s refusal to engage in animal experiments or vivisection did not hinder his fame worldwide. His studies and descriptions of various pathologies contributed immensely to the advancement of neurology. Prior to his research, extrapolating anatomical observations from animals to humans had led to conceptual errors. By focusing on human autopsies, Charcot rectified these misconceptions and established his prominent position in the field.

Charcot’s contradicting ethics were that while he disapproved studies involving animals, he did the sections on humans. His commitment to accurate observation and human autopsies solidified his renowned status as a pioneer in the field, earning recognition for his detailed descriptions of various pathologies.

Studies in Neurology

Charcot, is known as the father of modern neurology, possessed a distinct fascination with pathology and a deep appreciation for anatomical discoveries. Throughout his career, he pioneered novel approaches to classify neurological diseases, relying on his astute observations and anatomo-clinical correlations. Even today, more than a century after his passing, many of his methods and initial concepts remain integral to the field of neurology. As Joseph Babinski, one of his students, remarked, removing Charcot’s discoveries from neurology would render it unrecognizable.

A notable contribution of Charcot’s was his utilization of the anatomo-clinical method in neurology, highlighting the intricate relationship between anatomy and clinical presentations. Despite being perceived as distant and impatient in his interpersonal interactions, Charcot’s genuine fondness for animals remained a unique aspect of his character. Paradoxically, while engrossed in neuropathology and anatomo-clinical correlations, he disapproved of studies involving non-human animal species.

Charcot’s influence on the field of neurology is evident through numerous conditions that bear his name, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Charcot’s disease), hereditary sensory-motor neuropathy (Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease), tabes dorsalis arthropathy (Charcot’s arthropathy), and primary intracerebral hemorrhage (microaneurysms of Charcot-Bouchard). He also described other significant conditions such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and Tourette Syndrome. Notably, Charcot’s contributions extended beyond clinical correlations, as he made significant advancements in neuroanatomy, challenging prior knowledge based solely on animal dissections that did not always align with human findings.

Professor of anatomy and neurology

In 1872 Charcot became a professor of pathological anatomy at the University of Paris, and in 1882 – professor of neurology. His laboratory at L’Hôpital Salpêtrière had several thousand patients, more than half of whom suffered from neurological disorders. Charcot developed his own classification method of neurological disorders describing clinical features and performing autopsies.

As skilled pathologist Charcot recognized the relationship between clinical and anatomical findings. This method allowed him to correlate the clinical signs of multiple sclerosis (MS) with the pathological changes observed at autopsy. Gifted as an artist, Charcot described MS visually and supplemented his stories with illustrations of sclerotic plaques. He was not only extremely humane but also devoted to his patients. In his presence, he wouldn’t tolerate anything unkind being said about anyone.

He became the first physician to diagnose MS in a living patient, using the triad of nystagmus, intention tremor, and read speech to distinguish it from similar diseases. Today, the Charcot Prize is awarded every two years for advances in MS research.

In addition, Charcot documented cases of progressive motor symptoms characterized by convulsions, rigidity, contracture, bulbar involvement, and respiratory failure leading to death. He labelled this condition primary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and correctly identified anterior horn cell dysfunction as the underlying pathology.

In collaboration with his student Pierre Marie, Charcot studied patients whose pathology was incompatible with ALS, calling them neuropathy rather than myopathy. This led to the recognition of Charcot-Marie-Tooth, a peroneal form of muscular dystrophy, bearing their names.

Chair of Diseases of the Nervous System

Because of his ground-breaking achievements in the field of neurology Charcot received in1882 a prestigious appointment to the newly established Chair of Diseases of the Nervous System. This chair was specifically created by governmental decree to accommodate his expertise.

A daring move awaited Charcot in 1883 when he stood for election to the Academy of Sciences. Notably, the Academy had long condemned mesmerism, making his presentation on hypnosis a bold endeavour. However, Charcot’s assimilation of hypnosis to hysteria and his belief that hysteria constituted an organic disease granted him a measure of respectability. By framing hypnosis as a brain disorder mirroring hysteria, he avoided the forbidden topic of animal magnetism. Consequently, Charcot’s election to the Academy signalled a breakthrough, shattering the barriers that surrounded hypnosis and rendering it a legitimate subject for scientific exploration.

This was the pivotal moment which marked the emergence of psychology as an independent academic discipline.

Studies on Hysteria

Charcot, along with his disciple Paul Richer, utilized his method for organic neurological diseases to investigate hysteria. In 1878 Charcot’s friend Charles Richet, the recipient of 1913 Nobel Prize for medicine, convinced him to experiment with hypnosis on his patients. Several gifted female hysterical patients became his subjects, progressing through stages of “lethargy,” “catalepsy,” and “somnambulism” with distinct symptoms.

Rehabilitating hypnosis

When Charcot delved into the nature of hypnosis, he sought to establish further connections, given his previous association of hysteria with suggestibility. Remarkably, he discovered that his patients entered three distinct states of hypnosis: lethargy, catalepsy, and somnambulism. Lethargy resembled the state of fainting, transitioning to catalepsy once the subject’s eyes opened, resulting in limbs retaining any imposed position. Additionally, somnambulism exhibited a connection to hysteria through the manifestation of anaesthesia, often observed as “glove anaesthesia” or “sleeve anaesthesia”. Based on these observations, Charcot came to the conclusion that hypnosis represented an artificially induced modification of the nervous system exclusive to hysterical patients. It was primarily this scientific discourse that bestowed scientific credibility upon the previously taboo subject of hypnotism.

Turning mesmerism into hypnotism

A daring move awaited Charcot in 1883 when he stood for election to the Academy of Sciences. Notably, the Academy had long condemned mesmerism, making his presentation on hypnosis a bold endeavour. However, Charcot’s assimilation of hypnosis to hysteria and his belief that hysteria constituted an organic disease granted him a measure of respectability.

Charcot presented his findings to the Academie des Sciences in early 1882, an impressive feat considering the Academie’s prior condemnation of hypnotism. This groundbreaking paper granted hypnotism newfound respect, prompting numerous publications on the once shunned subject.

By framing hypnosis as a brain disorder mirroring hysteria, he avoided the forbidden topic of animal magnetism. Consequently, he shattered the barriers that surrounded hypnosis and rendered it a legitimate subject for scientific exploration.

This pivotal moment marked the emergence of psychology as an independent academic discipline, for the first time.

Traumatic versus psychogenic paralyses

Among Charcot’s remarkable achievements were his investigations on traumatic paralyses in 1884 and 1885. During his time, paralyses were predominantly attributed to nervous system lesions caused by accidents, though the concept of “psychic paralyses” had been proposed in England by B.C. Brodie in 1837 and Russel Reynolds in 1869. However, how could a purely psychological factor induce paralysis without the patient’s awareness or the possibility of feigning?

Charcot had previously examined the disparities between organic and hysterical paralyses. In 1884, three men with trauma-induced monoplegia of the arm were admitted to Salpetriere. Charcot showcased that while these paralyses differed from organic ones, they precisely aligned with hysterical paralyses. The next step involved experimentally reproducing similar paralyses under hypnosis. Charcot suggested to hypnotized subjects that their arms would become paralyzed, resulting in hypnotic paralyses mirroring spontaneous hysterical and posttraumatic cases.

Posttraumatic versus hypnotic paralyses

Charcot meticulously replicated these paralyses and even suggested their reversal. To demonstrate the effect of trauma, Charcot selected easily hypnotizable individuals and suggested that their arms would be paralyzed upon receiving a slap on the back in their waking state. The subjects exhibited posthypnotic amnesia and instant monoplegia when slapped, identical to posttraumatic monoplegia. Additionally, Charcot observed that certain subjects in permanent somnambulism experienced arm paralysis without verbal suggestion after being slapped. This illustrated the mechanism of posttraumatic paralysis. Charcot deemed the nervous shock following trauma akin to a hypnotic state, enabling individual autosuggestion. Charcot concluded that his experimental research accurately depicted the condition he aimed to study.

He classified hysterical, posttraumatic, and hypnotic paralyses as dynamic paralyses, distinct from organic paralyses caused by nervous system lesions. Charcot replicated this demonstration with hysterical mutism and hysterical coxalgia through hypnotism. In 1892, he distinguished “dynamic amnesia” with recoverable memories under hypnosis from “organic amnesia” where recovery was impossible.

Tree stages of hypnosis

Remarkably, he discovered that his patients entered three distinct states of hypnosis: lethargy, catalepsy, and somnambulism. Lethargy resembled the inert state of fainting in hysteria, transitioning to catalepsy once the subject’s eyes opened, resulting in limbs retaining any imposed position. Drawing a parallel to hysterical paralysis, Charcot noted that aggressive thoughts and actions followed if the limbs were positioned aggressively.

Additionally, somnambulism exhibited a connection to hysteria through the manifestation of anaesthesia, often observed as “glove anaesthesia” or “sleeve anaesthesia” among hysterics. Thus, Charcot concluded that hypnosis represented an artificially induced modification of the nervous system exclusive to hysterical patients, manifesting in the aforementioned distinct phases. It was primarily this scientific discourse that bestowed scientific credibility upon the previously taboo subject of hypnotism.

Charcot challenged the prevailing medical opinion that hysteria rarely afflicted men. He argued that hysteria, an organic disorder, could arise from trauma and manifest itself in “models of masculinity,” such as railroad engineers or soldiers. This pioneering perspective paved the way for understanding neurological symptoms resulting from trauma.

The Drama Teacher

Charcot revolutionized traditional ward lists by performing dramatic clinical demonstrations and patient interviews on the brilliantly lit stage of the Salpêtrière amphitheatre. His hypnotic experiments and clinical manifestations attracted public attention. The “Hysteria Show” seduced Parisian intellectuals and aristocracy, giving birth to hysteria fashion. This innovative teaching method influenced Sigmund Freud, who was one of Charcot’s neuroscience students, in his research into the psychological origins of neuroses. Charcot had such an influence on Freud that he named his first son after his revered teacher.

Shrouded in an aura of mystery and known as a “miracle” cure, his insights into his patients’ ailments seemed unsettling. In the case of hysterical paralysis, he simply told the patient to take off his crutches and walk.

The magician of hypnosis

The public perceived Charcot as a man who delved into the depths of the human mind, earning him the nickname “Napoleon of Neuroses.” He became closely associated with the discovery and interpretation of various neurological conditions, including hysteria, hypnotism, dual personality, catalepsy, and somnambulism.

Charcot delighted in the dedication of both his students and patients, to the extent that his patron saint’s day, Saint Martin, on November 11th, was celebrated at the Salpetriere with entertaining festivities.

Curious tales circulated about Charcot’s influence over the hysterical young women of the Salpetriere and the intriguing events that took place there. During a patients’ ball, for example, the unintended sound of a gong caused many hysterical women to instantly fall into cataleptic states, maintaining the poses they were in when the gong sounded. Charcot’s piercing gaze was renowned for its ability to penetrate the depths of the past, retrospectively diagnosing neurological conditions in cripples depicted in artworks. He founded journals like the Iconographie de la Salpetriere and the Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpetriere, pioneering the fusion of art and medicine.

Thursday Lectures

Charcot’s lectures, attended by high society and reporters, boosted hypnosis into the popular press. Consequently, vivid descriptions of cataleptic patients filled the media, followed by sensational, often false, tales of clairvoyance and sexual seduction during hypnosis. The stage hypnotists even rode the wave of Charcot’s fame, advertising their shows as “in the manner of Charcot at the Salpêtrière.”

The spellbinding effect of Charcot’s teaching extended to laymen, many physicians, and foreign visitors like Sigmund Freud, who spent several months at the Salpetriere.

Through hypnosis, Charcot made noteworthy discoveries, including the proof that psychological factors alone could induce certain paralyses. He achieved this by suggesting paralysis to hypnotized patients, showcasing their identical symptoms to organic paralyses. Furthermore, he distinguished between “dynamic amnesia,” allowing memory recovery, and “organic amnesia,” where memories remained irretrievable.

Expert on hysteria

Various ailments that fell under the umbrella of “hysteria” became Charcot’s specialty. This mental disorder was a collective term for several organic and neurotic disorders. Hallucinations, loss of consciousness, inorganic paralysis, and convulsions often led to individuals being labelled hysterical. Today, what once fell under the category of “hysteria” is classified as PTSD, Briquet syndrome, conversion disorder, and dissociative disorder. Trying to bring order to chaos, Charcot defined high hysteria as three stages: fainting, convulsions and intense emotional manifestations. Sometimes there was a fourth stage of delirium, lasting several days.

Although Charcot believed that hysteria was an organic disorder associated with brain pathology, the progressive aspect of his work challenged the prevailing notion that only women were prone to hysterical conditions, the term itself being derived from the Greek word for “womb”. Among the subclasses of hysterics, sleepwalkers and fugue-prone people stood out. During these states, they temporarily forgot their identity and took on an alternate personality, with limited

Animosities

Visitors who envied Charcot during their brief encounters in Paris remained unaware of the powerful enemies surrounding him. The clergy and Catholics branded him an atheist, partly due to his replacement of nuns with lay nurses at the Salpetriere. However, even some atheists found him too spiritual. Magnetists publicly accused him of charlatanism, while political and societal circles harbored fierce animosity towards him.

Among neurologists, some who admired Charcot while he focused on neuropathology deserted him when he delved into the study of hypnotism and conducted dramatic experiments with hysterical patients.

Charcot faced an ongoing battle against the Nancy School, gradually losing ground to his opponents. Bernheim sarcastically proclaimed that among the thousands of patients he hypnotized, only one displayed the three stages described by Charcot—a woman who had spent three years at the Salpetriere. Charcot also faced intense hatred from some of his medical colleagues, and even his former disciples.

The extreme opinions and fascination surrounding Charcot, combined with the intense enmities he garnered, hindered a true assessment of the value of his work during his lifetime. Even with the passage of time, this task remains challenging. Hence, it is necessary to distinguish the various fields of his activity.

Critical Review

Charcot did not pioneer the use of hypnosis for treating hysteria. Beginning with Anton Mesmer the early hypnotists had already observed the profound hypnotisability of hysteric patients achieving spectacular healings.

Biased judgment

Charcot’s approach lacked scientific rigor, relying on subjects who confirmed their preconceived notions. Charcot believed that the three phases of hypnosis occurred spontaneously, but it is likely that both patients and assistants merely presented what he anticipated. Selecting about a dozen female hysterics as their subjects, all inpatients of the hospital, they displayed the desired three phases of hypnosis to varying degrees. In fact, it is possible that the patients sought to please Charcot by adhering to his suggestions, given the close-knit, bustling environment of the Salpêtrière.

Doctors and patients intermingled, creating opportunities for overheard conversations and subsequent gossip among patients. Consequently, patients became aware of the expectations in the experiments. It remains unclear how frequently Charcot himself conducted hypnosis on patients, as it is plausible that his assistants prepared them in advance. In such cases, the patients may have received guidance from the assistants regarding what the esteemed doctor anticipated from them. Regrettably, no independent researchers have managed to validate his findings.

Janet’s criticism

Janet demonstrated that the alleged “three stages of hypnosis” were merely the result of training by magnetizers. Charcot, forgetting the early history of magnetism and hypnotism, believed he made new discoveries in his hypnotized patients, more so than Bernheim. Another distortion was the collective spirit prevalent in the Salpetriere—a closed community housing not only elderly women but also special wards for young, attractive, and cunning hysterical patients. This environment fostered mental contagion, ideal for demonstrations to students and Charcot’s lectures attended by Tout-Paris.

Due to Charcot’s paternalistic attitude and despotic treatment of students, his staff dared not contradict him. They presented what they believed he wanted to see after rehearsing demonstrations, even discussing cases in front of patients. This created an atmosphere of mutual suggestion among Charcot, his collaborators, and patients, warranting a thorough sociological analysis. Janet emphasized that Charcot’s descriptions of hysteria and hypnotism were based on a limited number of patients.

Final Years

Charcot’s final years were marred by angina pectoris, a result of his sedentary lifestyle, lack of exercise, and excessive cigar smoking. in 1893 he died of heart failure and died suddenly. His funeral took place in the chapel of his alma mater, Salpêtrière, and he was buried in the Montmartre cemetery.

Reluctantly, his son Jean-Baptise followed in his footsteps and became a doctor and renowned marine explorer. Jean-Baptise thought that this was the best way to honor his father’s memory, because the Charcot name would be doubly respected. As a testament to his father’s legacy, Charcot Island in Antarctica was named in his honor.

in 1895 his students financed the installation of a bronze statue of Charcot at the entrance to the Salpêtrière in his honor. Unfortunately, after the Germans occupied Paris during World War II, the statue was unfortunately removed and melted down for munitions.

Charcot’s three careers

Hence, it becomes necessary to distinguish between the various fields of Charcot’s activity. Firstly, his contributions as an internist and anatomo-pathologist to the understanding of pulmonary and kidney diseases are often overlooked. His lectures on diseases of old age became classics in geriatrics. Secondly, in neurology, his second career, he made remarkable discoveries that solidify his enduring fame. These include the delineation of multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (known as “Charcot’s disease”), locomotor ataxia and its unique arthropathies (“Charcot’s joints”), as well as his work on cerebral and spinal cord localizations, and aphasia.

On the other hand, evaluating Charcot’s “third career,” his exploration of hysteria, proves immensely challenging. Despite controversies this particular aspect contributed significantly to his contemporary acclaim. It is this breakthrough that will endure in the memory of mankind, even if his neurological work fades over centuries.

Summary

The extreme opinions surrounding Charcot, both fascination and fierce enmities, hindered a true assessment of his work during his lifetime. Contrary to expectations, time hasn’t made this task much easier.

The publication of his complete works, which had been planned in fifteen volumes, was abandoned after the volume IX. According to Lyubimov, Charcot’s student, had left a considerable amount of literary works: memoirs, illustrated travelogues, critical studies on philosophical and literary works, all of which he did not want published in his lifetime. Lyubimov adds that Charcot’s true personality could not have been known before their publication. However, none of these writings has ever been printed.

His son Jean (1867- 1936), who had studied medicine to please the father, gave up later this profession and became famous as a seafarer and explorer of the South Pole.

Charcot’s precious library was donated by his son to the Salpetriere and gradually fell into oblivion, as well as did the Musee Charcot.