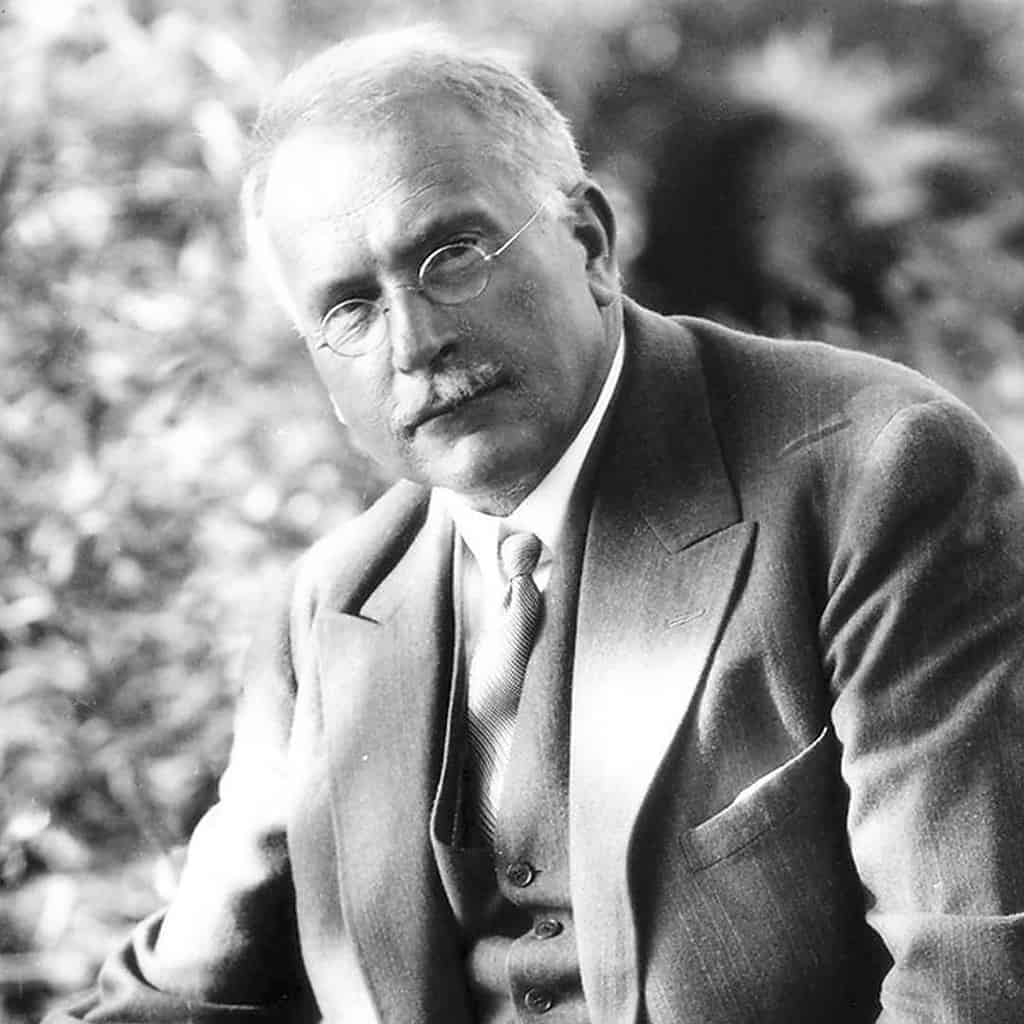

Introduction to C.G. Jung biography

Jung was a man of paradox, a rational scientist, and the explorer of the irrational and esoteric, undeterred by societal conventions. He embraced both individualism and universal embodiment pursuing his human potential while living uniquely, unbothered by upsetting others. In his view, exclusively rational psychology was inadequate and unjustified. In his opinion the psyche was not related to time and space crossing the border of materialism. Observing phenomena related to each other by the content and not causally related he introduced the term “synchronicity”, contradicting again the foundation of temporary science based on causality.

He followed his truth, diverging from the prejudices of his time feeling obliged to inform society of his discoveries. Jung’s destiny was to swim against the tide making him an intriguing character. He represented the opinion that some truths may not be accepted in his time, but in the future they might be.

In contrary to Freud, Jung was a deeply introverted man, who delved into dreams and inner experiences. His introspection stemmed from unique circumstances of his birth and upbringing. Therefore, understanding Jungian psychology requires examining his life and personality.

Jung. Childhood

Carl Jung was born in Kesswil, Switzerland on 26 July 1875 to Paul Jung and Emilie Jung born Preiswerk.

Paul Achiles Jung, Carl’s father, was the youngest son of a noted German-Swiss professor of medicine at the University of Basel. In contrary, Paul decided to study theology and became later a rural pastor in the Swiss Reformed Church.

Emilie, Carl’s mother, grew up in a large family with Swiss roots. Her father, Samuel Preiswerk, was a head of the Reformed clergy in Basel, a Hebraist, author, and editor.

The insecure bond

Jung spent his childhood in a parish in rural Switzerland. Prior to Carl’s birth his parents lost two stillborn girls and a son who died after living only five days. In consequence, at the time of Carl’s birth, his mother Emilie suffered from depression. At the same time his father Paul Achilles Jung, was at odds with his Christian beliefs. Despite having lost his faith, Paul Jung kept his position in the church also growing more disappointed and depressed.

The marriage of his parents was full of tensions. His mother was eccentric and emotionally instable. Carl notice that she was “normal” during the day but became strange and mysterious at night. Following the Preiswerk spiritualism she claimed spirits visited her room. After having developed a severe depression, she was admitted for few months to the hospital as Carl was three years old. Carl’s father Paul Achilles Jung was a warm-hearted man but undecisive and weak.

Based on these experiences, Carl associated women with unreliability and men with weakness. Missing a strong father figure in his childhood, Jung later projected his paternal archetype onto Freud who became his mentor.

Carl’s introspection abilities

Jung was a lonely and extremely introverted child. From an early age he possessed a genius for introspection. At the age of seven he used to spend time sitting on a big stone in the garden of the parish. He called the stone “his stone”. Sitting on the stone he asked himself “Am I it, or is it I? Am I the one who is sitting on the stone, or am I the stone on which he is sitting?” (C.G. Jung, Memories, Dreams and Reflections (MDR).

It’s astonishing that a boy of seven years had developed such abstract way of thinking mirroring the psychoanalytical model of projection.

Childhood memories

Jung was a solitary and introverted child. Living isolated in the parish, Carl read all books he found in his father’s library. He created a secret language and used to carve symbols and images. Later these experiences inspired his theory of archetypes and the concept of the collective unconscious.

Observing himself he believed he had two personalities, one of a modern Swiss and the other of a dignified and authoritative person from the past.

At the age of twelve, Jung’s academic journey was marked by a turning point. In a scramble Carl was hit by a school mate and fainted. Upon regaining consciousness an idea appeared in his mind that the fainting was a perfect reason to avoid school. His parents believed that he developed epilepsy and kept him at home. However, hearing his father expressing worries about Carl’s future, he was determined to go back to school and to overcome the fainting spells. Jung described this experience as his early insight into the nature of neurosis.

University studies and early career

Influenced by family tradition Jung initially wanted to become a preacher. Later he changed his mind and decided to study archaeology. Finally, for opportunistic reasons he began to study medicine at the University of Basel. Medicine as a combination of biology and spirituality turned out to be a good compromise for him. Barely a year later in 1896, his father Paul died and left the family near destitute. They were helped out by relatives who also contributed to Jung’s studies.

In 1900, Jung moved to Zürich and began working at the Burghölzli Psychiatric Hospital under Eugen Bleuler. 1903 he wrote his dissertation titled “On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena”. His research was based on the analysis of Jung’s cousin Hélène Preiswerk, a mediumistic medium. Later Jung moved to Paris and participated in the lectures of Pierre Janet, a distinct French psychiatrist.

Marriage

Jung had married Emma Rauschenbach (1882-1955), the daughter of a rich industrialist. Between 1904 and 1914 they had five: four daughters and a son. Initially, their residence was a flat in Burghölzli. However, in 1908, they relocated to a splendid house they designed and constructed by the lakeside in Küsnacht, where they would spend the remainder of their lives.

Friendship with Freud

In 1904, Jung published “Studies in Word-Association” and sent its copy to Sigmund Freud. One year later he visited Freud in Vienna. From that time onward, he established a close friendship and a strong professional association with Freud. For six years he was the advocate of psychoanalysis and became the president of “The International Psychoanalytic Association”. In 1912, however, Jung published “Psychology of the Unconscious”, which expressed different view on the main human drive called “libido”. Contrary to Freud’s dogma,

The book manifested the developing theoretical divergence between the two. Consequently, their personal and professional relationship went to pieces. After the culminating break in 1913, Jung went through a difficult and pivotal psychological transformation resembling a psychosis.

Jung’s “confrontation with the unconscious”

During Jung’s critical phase, the actual nature of his experience remains a topic of debate. Henri Ellenberger, the author of the monumental work “The discovery of the Unconscious” proposes that Jung underwent a “creative illness” much like Freud at a similar age. This condition emerges after intense intellectual activity and resembles neurosis or, in severe cases, psychosis. The individual struggles with unresolved issues, feeling isolated and beyond help. The disturbance can endure for four to five years. Recovery occurs spontaneously, accompanied by euphoria and a profound transformation of personality. The person gains insights into important truths and feels a duty to share them with the world. Jung’s experience mirrors that of shamans, mystics, artists, writers, and philosophers. The theme of the descent into the underworld and the return also occurs in the epic of Gilgamesh, Virgil’s Adenoid, and Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Jung and Freud. The middle age transformation

But the most interesting parallel is, as we have already noted, the neurotic breakdown suffered by Freud in the 1890s which he cured with his own self-analysis, discovering in the process the basic principles of psychoanalysis – the use of free association, the dream analysis, the role of sexuality in the aetiology of neurotic illnesses, the stages of libidinal development in childhood, the repression of forbidden wishes, and so on.

On their recovery, both men published major and original books: Freud’s “The Interpretation of Dreams” appeared in 1900 when he was 45, and Jung’s “Psychological Types” in 1921 when he was 46. Thus, it was that most of Freud’s ideas were already developed and had become fixed before he met Jung, whilst most of Jung’s were developed after he had found the courage to to depart from Freud and suffer the consequences of his loss. If the six years of their friendship was a period of discovery and preparation for Jung, for Freud it was a time of retrenchment, during which he became increasingly intolerant of those who would revise his ideas, which for him had become matters of indisputable fact.

Breaking with Freud’s ideas

During this transformative phase, Jung rejected Freud’s reductionist theories and laid the groundwork for his own psychoanalytical theory. With the vigour of someone emerging from a creative illness, Jung delved back into the realms of myth, philosophy, and religion, seeking objective parallels to his experiences.

He argued that in the pursuit of understanding the human psyche, one must consider more than just sexual drives and repressed desires. Through a comprehensive historical review, he identified two fundamental psychological orientations: introversion and extraversion. Introversion involves an inward focus, retreating from the external world into the inner realm. On the other hand, extraversion entails an outward movement, directing interest towards the objective reality outside. Jung believed that his differences with Freud stemmed from his own introversion contrasting Freud’s extraversion.

Psychological types

The result of this intensive effort was his book, “Psychological Types”. Within its pages, Jung embarked on organizing his thoughts on the structure and function of the psyche while examining the fundamental differences between himself, Adler, and Freud.

While this explanation holds some truth, it fails to give due consideration to other significant factors. Both men hailed from vastly different backgrounds. Freud, with his Jewish-urban socialization, was nurtured by a young and beautiful mother and received an education rooted in progressive traditions, and naturally gravitated towards science. In contrast, Jung, a Protestant, had an insecure bond with his depressed mother, and was deeply influenced by theology and Romantic idealism. It is unsurprising that Freud adopted a sceptical empiricist approach, believing in the universal importance of the Oedipus complex, while Jung remained committed to the spiritual realm, asserting that the Oedipus complex lacked universal validity.

The subjectivity of the empirical

Another noteworthy distinction lies in their temporal perspectives. Freud tended to look backward, focusing on adaptive concerns and goals, while Jung inclined to look forward, emphasizing adaptive concerns and goals. This contrast becomes evident not only in their approaches to art but also in their approaches to mental illness. Jung came to nub of the matter when rehearsing his differences with Freud. In 1920 he wrote:

“Philosophical criticism has helped me to see every psychology – my own included – has the character of a subjective confession ... Even when I am dealing with empirical, I’m necessarily speaking about myself” (CW IV, para. 774).

DR. GREGOR KOWAL

Senior Consultant in Psychiatry,

Psychotherapy And Family Medicine

(German Board)

Call +971 4 457 4240

Sources

Collected Works of C.G. Jung, The First Complete English Edition of the Works of C.G. Jung. Archived from the original on 2014-01-16. Retrieved 2014-01-20. Taylor & Francis

Jung, C.G.; Aniela Jaffé (1965). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. New York: Random House. p. v.

Jung, Carl Gustav. Psychology and the Occult. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978

Bair, Deirdre (2003). Jung: A Biography. New York: Back Bay Books.

Gay, Peter (1995). Freud: A Life for Our Time. London: Papermac.

The BBC interviewed Jung for Face to Face with John Freeman at Jung’s home in Zurich in 1959

Carl Jung (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Collected Works, Volume 9, Part 1. Princeton University Press